A pro forma record of financial transactions from this era could illuminate how businesses, individuals, and even governments managed their resources. It could also reveal the types of goods and services exchanged, lending insights into daily life and the scale of commerce. Such a model could be invaluable for educational purposes, allowing students and researchers to visualize ancient financial systems in a concrete way. Furthermore, it could inspire creative explorations of ancient history in literature and other media.

This exploration delves further into the world of ancient finance, considering the practical aspects of record-keeping in the Roman Empire and its surrounding regions. Topics covered include the use of materials like papyrus and clay tablets, the role of scribes and accountants, common currencies and units of measurement, and the types of transactions that would likely have been recorded.

1. Transactions

Transactions form the core of any financial record, including a hypothetical first-century bank statement template. While modern transactions primarily involve currency, first-century exchanges frequently involved bartering goods and services. Consider a farmer trading a portion of their grain harvest for a craftsman’s pottery or a merchant exchanging imported spices for locally produced textiles. These transactions, though different in form from modern monetary exchanges, represent the fundamental flow of goods and services within an economy. Documenting these exchanges, whether through rudimentary notations on clay tablets or more formalized entries on papyrus scrolls, provides the basis for understanding economic activity in that era.

Reconstructing these transactions requires examining archaeological evidence and historical texts for clues about common goods, trade routes, and the relative value of different commodities. For example, inscriptions detailing temple offerings might reveal the types of agricultural products cultivated, while amphorae fragments discovered in shipwrecks suggest the movement of wine and olive oil across regions. Analyzing these fragments allows historians to piece together a picture of trade networks and the types of transactions documented in a hypothetical first-century financial record. The frequency and volume of certain transactions can also shed light on economic prosperity, regional specialization, and even social hierarchies.

Understanding the nature of transactions offers crucial insight into the workings of ancient economies. Challenges arise from the limited surviving evidence and the difficulty of interpreting incomplete records. However, the pursuit of reconstructing these transactions and incorporating them into a conceptual framework, such as a first-century bank statement template, provides a valuable lens through which to examine the past. This approach offers a tangible way to connect modern financial practices with their ancient predecessors, enhancing our understanding of economic development over time.

2. Currency/units

Currency and units of measurement are fundamental components of any financial record, including a hypothetical first-century bank statement template. While modern banking relies heavily on standardized currencies, the first century CE presented a more complex landscape. The Roman denarius, a silver coin, circulated widely throughout the Roman Empire, but local currencies and barter systems continued to play significant roles in many regions. In addition to monetary units, various units of weight and volume, such as the Roman pound (libra) and the amphora, were essential for quantifying goods in transactions. Reconstructing a first-century financial record requires understanding this diverse system of measurement and its implications for recording exchanges.

Consider the challenges of recording a transaction involving grain. A hypothetical record might specify a quantity of wheat measured in modii, a Roman unit of dry volume. However, the value of that wheat could fluctuate based on local market conditions, the quality of the harvest, and the specific terms of the exchange. Furthermore, transactions might involve a combination of currency and bartered goods, necessitating careful documentation of both the quantity and type of items exchanged. For example, a record might detail the sale of a quantity of olive oil measured in amphorae, partially paid in denarii and partially exchanged for a specific quantity of wool. This complexity underscores the importance of understanding both currency and units of measurement when interpreting ancient financial records.

Reconstructing the use of currency and units of measurement in the first century CE provides valuable insights into the economic complexities of the Roman Empire and its surrounding regions. While surviving records offer glimpses into these practices, challenges remain in interpreting incomplete and fragmented evidence. Developing a comprehensive understanding of the interplay between currency, units of measurement, and the recording of transactions allows for a more nuanced interpretation of ancient economic activities. This understanding can inform the creation of a hypothetical first-century bank statement template, offering a tangible way to connect modern financial practices with their historical antecedents.

3. Materials (papyrus, clay)

The physical form of any record, especially in the context of a hypothetical first-century bank statement template, dictates its longevity, portability, and the methods used to create it. Materials available in the first century CE for record-keeping included papyrus and clay, each with distinct properties influencing how financial transactions might have been documented. Understanding these materials is crucial for envisioning the practical aspects of ancient record-keeping.

- Papyrus:Papyrus, manufactured from the papyrus plant, offered a relatively lightweight and portable writing surface. While more perishable than clay, papyrus facilitated longer and more complex records. Imagine a roll of papyrus detailing daily transactions in a bustling Roman marketplace, recording sales of goods like olive oil and wine. Its flexibility allowed for extended entries, potentially including details like customer names, quantities, and prices.

- Clay Tablets:Clay tablets, widely used in Mesopotamia and other regions, provided a durable but less portable option. Their rigid structure limited the length of individual entries, perhaps suitable for summarizing daily totals or recording individual debts. Envision a merchant using a stylus to etch cuneiform symbols onto a damp clay tablet, marking the delivery of a shipment of grain. While less convenient for extensive records, clays resilience ensured preservation in certain environments, offering valuable insights for archaeologists today.

- Durability and Preservation:The contrasting durability of papyrus and clay directly impacted the likelihood of preservation. Papyrus, susceptible to decay, survives primarily in arid climates, like those found in Egypt. Conversely, fired clay tablets withstand harsher conditions, increasing their chances of discovery across diverse archaeological sites. This difference significantly influences the available evidence for reconstructing ancient record-keeping practices.

- Format and Structure:The choice of material influenced the structure and organization of records. Papyrus scrolls permitted continuous writing, potentially facilitating chronological entries or the grouping of similar transactions. Clay tablets, with their limited surface area, might have encouraged more concise notations, perhaps utilizing abbreviations or symbols. These material constraints likely shaped the development of record-keeping systems and how information was organized.

Considering the properties of papyrus and clay illuminates the practical challenges and possibilities of creating and maintaining financial records in the first century CE. These materials, each with inherent limitations and advantages, shaped the development of record-keeping practices and, by extension, the potential form of a hypothetical first-century bank statement template. Analyzing these material constraints helps bridge the gap between our modern understanding of financial documentation and the realities of ancient record-keeping.

4. Record-keeping methods

Record-keeping methods represent a critical link to understanding a hypothetical first-century bank statement template. While no standardized template existed, the methods employed dictated the structure and content of financial records. These methods, influenced by available materials and societal complexity, provide crucial context for reconstructing ancient financial practices. Consider the impact of different methods on the form and function of such records.

Notational systems played a significant role. Simple tallies on clay tablets might suffice for tracking basic debts and credits in smaller communities. However, more complex systems, such as Roman numerals or early forms of accounting, become necessary for managing larger volumes of transactions or diverse commodities. Imagine a Roman merchant tracking shipments of goods across the Mediterranean. Detailed records, potentially utilizing specialized symbols or abbreviations, become essential for managing inventory, calculating profits, and ensuring accurate accounting. The development of these notational systems directly influenced the potential complexity and informational richness of a hypothetical first-century bank statement.

The organization of records further reflects prevailing methods. Chronological entries, perhaps grouped by customer or commodity, offer one approach. Alternatively, records might focus on specific projects or timeframes, such as agricultural cycles or tax collection periods. Consider a Roman administrator managing public works projects. Detailed records, organized by project and expenditure type, become crucial for accountability and resource allocation. These organizational principles, influenced by administrative needs and record-keeping practices, shape the hypothetical structure of a first-century financial record, providing insights into the practicalities of managing financial affairs in that era.

Understanding record-keeping methods provides crucial insights into the potential form and function of a hypothetical first-century bank statement template. Analyzing these methods, alongside material constraints and notational systems, allows for a more nuanced interpretation of ancient financial practices. This understanding offers a valuable framework for reconstructing how individuals, businesses, and governments managed their economic activities in the first century CE, bridging the gap between modern financial concepts and their historical antecedents. The challenges of interpreting incomplete evidence remain, underscoring the importance of continued research and analysis in this area.

5. Scribes/accountants

Scribes and accountants played a crucial role in ancient record-keeping, forming a direct link to the conceptual framework of a “first century bank statement template.” Although the structured format of modern bank statements did not exist, these individuals fulfilled essential functions in managing financial transactions and maintaining records. Exploring their roles provides valuable insight into the practicalities of ancient financial administration.

- Literacy and Numeracy:Scribes possessed the literacy skills necessary to document transactions, agreements, and other financial matters. Their expertise extended to numerical systems, enabling calculations for trade, taxation, and resource management. In the context of a hypothetical first-century bank statement, scribes would have been responsible for recording the details of transactions, calculating totals, and maintaining accurate records. Their literacy and numeracy formed the backbone of ancient financial administration.

- Record Management and Organization:Accountants, whether specialized individuals or those fulfilling such duties alongside other responsibilities, developed systems for organizing and retrieving financial information. These systems, whether simple lists or more complex ledgers, facilitated the management of debts, credits, and resource allocation. Imagine an accountant in a Roman villa overseeing the estate’s finances. Detailed records, perhaps organized by category or timeframe, provided essential information for managing expenditures and revenues. This organizational role prefigures aspects of modern accounting practices.

- Materials and Tools:Scribes and accountants utilized the materials and tools available in their respective times and places. Clay tablets, papyrus scrolls, styluses, and inkwells formed the essential toolkit for recording transactions. Consider a scribe in ancient Egypt meticulously documenting grain harvests on papyrus. Their skilled use of these tools allowed for the creation of durable and detailed records, crucial for administrative and economic purposes. These materials and tools shaped the form and content of ancient financial records.

- Trust and Authority:The role of scribes and accountants relied heavily on trust and authority. Accurate record-keeping was essential for maintaining financial stability and preventing disputes. In a society where oral agreements were common, written records provided a crucial form of verification. The authority vested in these individuals underscores their importance in managing economic activities and maintaining social order. Their trustworthiness contributed to the reliability of financial records.

The roles of scribes and accountants in the first century CE offer valuable insights into how financial information was managed and recorded. Understanding their skills, responsibilities, and the tools they employed provides context for envisioning the hypothetical structure and content of a “first century bank statement template.” This exploration bridges the gap between modern financial administration and its ancient predecessors, highlighting the enduring importance of accurate record-keeping across different eras and societies.

6. Potential Contents

Reconstructing the potential contents of a hypothetical “first century bank statement template” requires careful consideration of the types of financial transactions common in that era. While no standardized format existed, the information captured within such a record would likely reflect the economic activities of individuals, businesses, and potentially even government entities. Exploring these potential contents provides valuable insights into ancient financial practices.

- Commodities and Services:A central component of any financial record involves the goods and services exchanged. A hypothetical first-century record might detail transactions involving agricultural products like grain, olive oil, or wine, as well as livestock, textiles, and crafted goods. Services, such as transportation, labor, or construction, might also be documented, potentially specifying the duration or nature of the service provided. Examples could include a record of grain deliveries to a Roman granary, payment for a carpenter’s services in building a house, or an entry documenting the sale of livestock at a market. These entries, though likely lacking the precise numerical values of modern accounting, provide a glimpse into the economic activities of the time.

- Currency and Units of Measurement:Financial records necessitate quantifying transactions using established units of measurement. In the first century CE, this involved a complex interplay of currencies and units specific to different regions and commodities. Roman denarii might feature alongside local currencies, while units of volume (e.g., amphorae for liquids) and weight (e.g., librae for solids) specified quantities of goods. A hypothetical record might document the sale of a certain number of amphorae of olive oil paid for in denarii, or the exchange of a specified weight of wool for a quantity of grain. Understanding these units is crucial for interpreting the economic value of transactions.

- Parties Involved:Identifying the parties involved in each transaction provides crucial context. Names of individuals, businesses, or government officials might be recorded, alongside their roles (e.g., buyer, seller, lender, borrower). A record of a loan might specify the lender, borrower, amount, and repayment terms, while a sales record might identify the buyer, seller, and the goods exchanged. These details offer insights into economic relationships and social structures.

- Dates and Locations:Contextualizing transactions with dates and locations adds depth to financial records. Recording the date of a transaction allows for tracking financial activities over time, while noting the location can reveal trade routes and regional economic patterns. A hypothetical record might document the arrival of a shipment of goods at a particular port on a specific date, or the sale of land in a specific region. These details provide valuable historical and geographical context.

By considering these potential contents, a clearer picture of a hypothetical “first century bank statement template” emerges. While such a document would likely differ significantly from modern bank statements in format and precision, it represents an attempt to capture and organize essential financial information. Analyzing these potential contents offers a valuable lens through which to examine the economic activities and record-keeping practices of the first century CE, furthering our understanding of ancient financial systems.

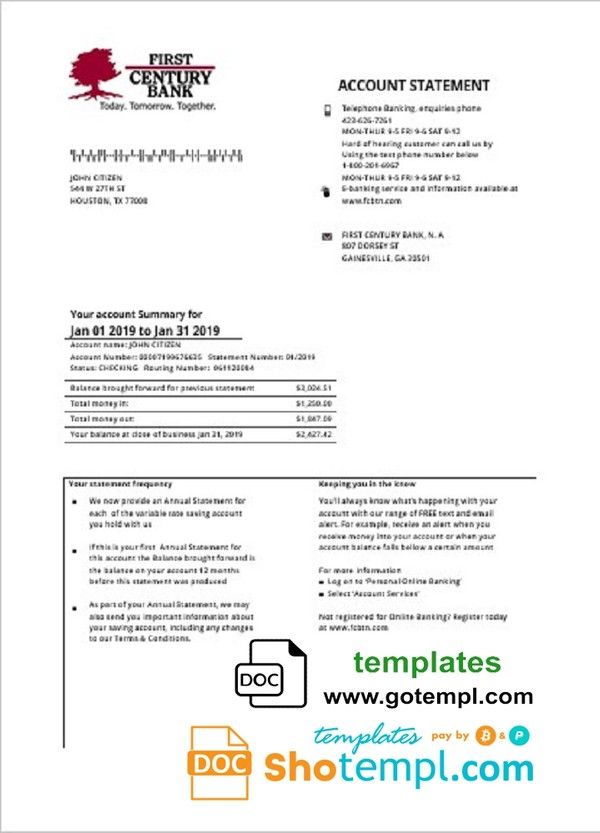

Key Components of a Hypothetical First Century CE Financial Record

Reconstructing a hypothetical financial record from the first century CE requires considering several key elements. While standardized “bank statements” did not exist, analyzing potential components offers insight into ancient financial practices.

1. Transactions: The core of any financial record lies in documenting the exchange of goods and services. These transactions, often involving barter, formed the basis of economic activity. Records might detail the trade of agricultural goods, livestock, crafted items, or services like labor or transport. Quantities and agreed-upon values, whether in currency or other units, formed crucial components of these entries.

2. Currency and Units: Quantifying transactions required established units of measurement. While Roman denarii circulated widely, local currencies and barter systems persisted. Units of weight (e.g., libra) and volume (e.g., modius or amphora) specified quantities of goods exchanged. Understanding these diverse systems is essential for interpreting transaction values.

3. Materials and Format: Available materials, primarily papyrus and clay tablets, dictated the format and longevity of records. Papyrus offered portability and allowed for extended entries, while clay provided durability but limited space. The chosen material influenced the structure and organization of information, from simple tallies to more complex notations.

4. Record Keepers: Scribes and individuals performing accounting functions played crucial roles. Scribal literacy and numeracy enabled the documentation and calculation of transactions. Accountants, whether dedicated or fulfilling multiple roles, developed organizational systems for managing financial information, prefiguring aspects of modern accounting practices.

5. Parties Involved: Identifying the parties involved, whether individuals, businesses, or government entities, provides context. Names and roles (buyer, seller, lender, borrower) helped track economic relationships and responsibilities within transactions. These details offer insights into social and economic structures.

6. Dates and Locations: Including dates and locations contextualizes transactions within specific timeframes and geographical areas. This information allows for tracking economic activity over time, identifying trade routes, and understanding regional economic patterns. Such details provide valuable historical and geographical context.

Reconstructing a hypothetical financial record from this era requires careful consideration of these interconnected elements. Although a formal “bank statement” template did not exist, these components represent the essential information likely captured to document and manage financial activities in the first century CE. Examining these elements offers a glimpse into the complexities of ancient economic practices.

How to Create a Hypothetical First Century CE Financial Record

Creating a plausible representation of a financial record from the first century CE requires a multi-faceted approach, acknowledging the absence of standardized templates while drawing upon historical evidence. This process blends historical research with imaginative reconstruction to produce a document that reflects the economic realities of the era.

1. Define the Scope: Determine the purpose and scope of the record. Will it represent the finances of an individual, a business, a government entity, or a specific project? Defining the scope clarifies the types of transactions and information to include.

2. Choose Materials and Format: Select appropriate materials, considering papyrus for extended records or clay tablets for shorter, more durable entries. The chosen material influences the format, whether a scroll, a series of tablets, or another form. This choice also impacts how information is organized.

3. Establish Units of Measurement: Determine the currency and units of measurement to employ. Research the prevalent currencies and units of the region and time period, considering Roman denarii, local currencies, and units of weight and volume. This ensures accurate representation of transaction values.

4. Develop a Notational System: Devise a system for recording transactions. This might involve adapting Roman numerals, using abbreviations, or creating symbols to represent common goods or services. The system should be clear, consistent, and appropriate for the chosen material and format.

5. Populate with Transactions: Based on the defined scope, populate the record with plausible transactions. Research common economic activities of the era, such as trade in agricultural goods, livestock, crafts, or services. Include details like quantities, agreed-upon values, and parties involved.

6. Incorporate Contextual Details: Add dates and locations to contextualize transactions. This provides historical and geographical depth, allowing for analysis of economic activity over time and across different regions. These details enhance the record’s realism and historical accuracy.

7. Consider the Record Keeper: Reflect on the role of the scribe or accountant responsible for creating and maintaining the record. This informs the style, organization, and level of detail included. Consider their literacy, numeracy skills, and the tools at their disposal.

Constructing such a document offers a valuable exercise in understanding ancient economic practices. This process involves combining historical research with creative interpretation to produce a plausible representation of a first-century financial record, providing a tangible connection to the economic realities of that era.

Exploring the concept of a “first century bank statement template” provides a valuable framework for understanding ancient economic practices. While such a standardized document did not exist, reconstructing a hypothetical version necessitates examining the materials, methods, and individuals involved in financial record-keeping during that era. Analyzing transactions, currency systems, record-keeping materials (papyrus, clay), and the roles of scribes and accountants reveals the complexities of managing financial affairs in the first century CE. This exploration illuminates how ancient societies documented economic activities, offering insights into trade, resource management, and social structures.

The absence of surviving examples underscores the challenges of interpreting fragmented historical evidence. However, engaging with this hypothetical framework fosters a deeper appreciation for the evolution of financial record-keeping. Further research into ancient economic practices remains crucial for refining our understanding of these systems. This exploration encourages continued investigation into the methods and materials used to document financial transactions in the past, offering a richer perspective on the development of modern economic systems.